Filed under: 3D, Equipment, Lighting, On Location, photogrammetry, RTI | Tags: Maori weaving, photogrammetry, RTI, TeRa

In January 2020 Mark Mudge and I traveled to the British Museum in London to document the only existing Māori canoe sail of its kind, made over 200 years ago. The imaging work was performed in collaboration with the New Zealand project Te Rā – The Māori Sail Whakaarahia anō te rā kaihau! – Raise up again billowing sail! funded by The Royal Society – Te Apārangi Marsden Fund.

The New Zealand team produced a 13½-minute video of the project that you can watch here: Imaging Te Rā at the British Museum 2020

helps prepare the sail for imaging

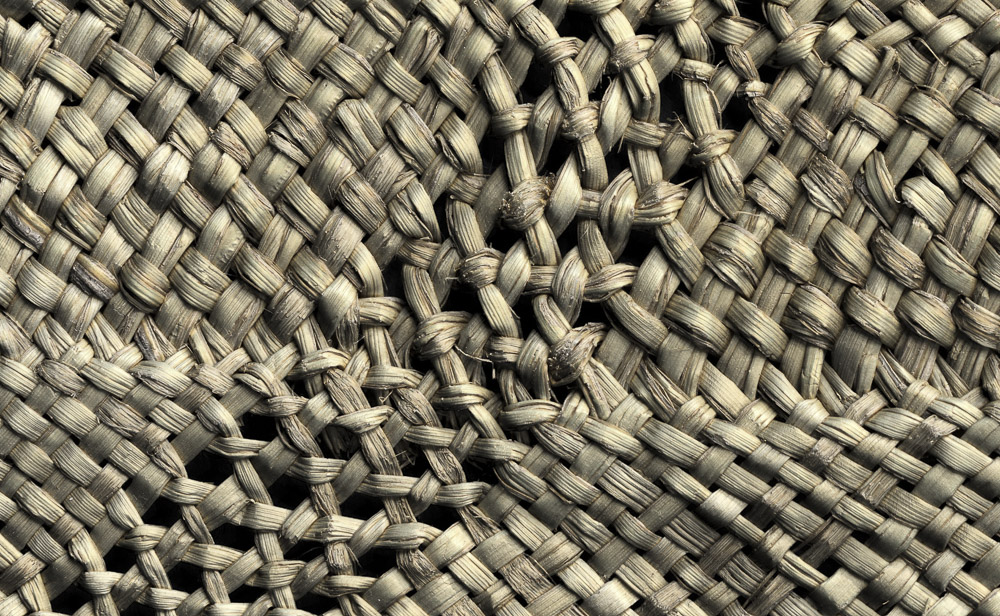

The construction and materials of the last known Māori sail, Te Rā, had not been identified, documented, or made publicly available, until this project put significant efforts into these identifications and documentation. Māori textile researchers from New Zealand brought in CHI to image the sail, which is made with fragile plant materials and feathers. The CHI team used both photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to help the experts examine and understand more about the delicately woven and perishable materials. The research team wanted to gain a greater understanding of how the Māori sailed the ocean and the intricacies of their weaving techniques.

We worked with the sail on site at the British Museum for 5 days.

The first day was all preparation: meeting the team, examining the sail, setting up equipment, testing lights, and troubleshooting. The second day was spent on the imaging. The initial preparation had begun back in the CHI studio in San Francisco, when Marlin Lum, Imaging Director, prepared for the intensive imaging project by creating a life-size paper template of the sail so the CHI team could work out the imaging logistics ahead of time. Marlin had also created an ingenious camera rig to manage the imaging and protect the fragile materials. Marlin’s rig was attached to a rental pro video slider unit that we picked up in London on the first morning.

At the museum collection facility, the sail was spread out on a protective foam core platform on the floor, covered by black paper. Because the sail has a pattern of holes in it, we performed tests on how best to mask out the holes so that they would be correctly modeled as holes in the final model. The black paper worked best. Over this the team positioned the trolley with its cantilevered arm that could move across and incrementally shoot the entire area, photo by photo. The camera height could be adjusted using a slider and the camera angle could be adjusted using a ball head.

Here is my project note from the morning of the second day:

“Light tests and light adjustments are done. We add a Speedlite to the mix of lights to deal with a corner that was a bit dark. We will trigger the Speedlite (Michael’s Canon 600) with the PocketWizard TT1 and TT5 combo and all 4 Monoblocks are set to slave mode. It takes a bit of time to tune everything in using the light meter and small adjustments. We feel now the entire sail is evenly lit and imaging can begin.”

Scale bars were placed around the small end of the sail as were color checkers. Using a Canon 5DSR with 24mm f2.8 IS USM lens, and shooting at 18 inches distance from the subject, the imaging began with a calibration pass with 90-landscape-270 rows – then returned to the 90 position for the remainder of the imaging in that pass.

The feathers that trim the sail presented a significant imaging challenge: they stick up, and there are knots and places where the material juts out. The camera focus was set manually to allow some extra depth of field above where the main body of the sail was laid out, so that these elements would remain in focus.

As the work progressed, I recorded this:

“We completed the second pass of the sail with a 50mm lens today and shot 3 RTIs of detail areas chosen by Donna from the Maori textile team. Then we had a crew come in to turn the sail over, and we prepped everything for the back side (which is actually more important for the weavers). We will begin shooting that first thing tomorrow.”

Image: © TeRa Project, Marsden Fund, 2020:

After completing the work on site each day, we returned to our London apartment and began the next step: processing the images of the sail. We have built the RTIs and some other high-resolution 2D outputs of the sail and shared them with the team. The detail is fantastic. We look forward to the team’s continued research and the publishing of their findings, along with our imaging results.

Special thanks to: Donna Campbell, co-Principle Investigator (co-PI) for the research project worked closely with us on site; Julie Adams, Curator of the Oceania Collections at the British Museum, hosted the imaging project; Michael O’Neill, a photographer from the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa; Kira Zumkley, a London-based heritage photographer and researcher; and Jill Hassell, museum assistant. Catherine Smith, co-PI on the project aided in logistics and overall project management.

You can read more about the sail in the research team’s blog and also the British Museum’s description of the sail from its online collection.

Filed under: Guest Blogger, Technology, Training, Workshops | Tags: 3D data, conservation, photogrammetry, Training

Lauren Fair is Associate Objects Conservator at Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library in Buffalo, New York. She also serves as Assistant Affiliated Faculty for the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC). Lauren was a participant in CHI’s NEH grant-sponsored 4-day training class in photogrammetry, August 8-11, 2016 at Buffalo State College. She posted an account of her experience in the class in her own blog, “A Conservation Affair.” Here is an excerpt from her fine post.

I have discovered the perfect way to decompress after a four-day intensive seminar on 3D photogrammetry: go to your friend’s cabin on a small island in a remote part of Canada. While you take in the fresh air and quiet of nature, you can then reflect on all that you have shoved into your brain in the past week – and feel pretty good about it!

I have discovered the perfect way to decompress after a four-day intensive seminar on 3D photogrammetry: go to your friend’s cabin on a small island in a remote part of Canada. While you take in the fresh air and quiet of nature, you can then reflect on all that you have shoved into your brain in the past week – and feel pretty good about it!

The Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) team – Mark, Carla, and Marlin – have done it again, in that they have taken their brilliance and passion for photography, cultural heritage, and documentation technologies, and formulated a successful workshop on 3D photogrammetry that effectively passes on their expertise and “best practice” methodologies.

The course was made possible by a Preservation and Access Education and Training grant awarded to CHI by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

(Read the rest of Lauren’s blog here.)

Filed under: Guest Blogger, Technology, Training | Tags: 3D data, conservation, photogrammetry, Training

Our guest blogger, Emily B. Frank, is currently pursuing a Joint MS in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and MA in History of Art at New York University, Institute of Fine Arts. Thank you, Emily!

I’ve been following the development and improvement of photogrammetry software for the past few years. As an objects conservation student with a growing interest in the role of digital imaging tools in the study and conservation of art, I’ve always found photogrammetry of theoretical interest. In my opinion, until recently the limited accuracy of the software and tools impeded widespread applications in conservation. With recent advances, this is no longer the case; sub 1/10th mm accuracy has changed the game.

This January, the stars aligned and I was able (and lucky) to participate in CHI’s January photogrammetry training. From January 11 to 14, I lived and breathed photogrammetry in CHI’s San Francisco studio. The four-day course was co-instructed by Carla Schroer, Mark Mudge, and Marlin Lum, who each brought something extraordinary to the experience.

For those of you that don’t know them personally, I’ll provide context; these guys are total gurus. Carla brings business and tech know-how from years of work in Silicon Valley earlier in her career. She has a warm and direct teaching style that is accessible no matter what your photography/imaging background. Mark is a true visionary; he is rigorous and inventive, and always carefully pushing the brink of what’s possible. Marlin is the photographer of the group and a master at fabricating the perfect tool/workstation for the capture of near-perfect source images. His never-ending positivity is contagious. Together they are practically unstoppable. It’s obvious that they love teaching and truly believe in the power of the tools they are sharing.

The class began with a brief theoretical introduction, then dove into practical aspects of capture and processing. We swiftly covered how to approach a range of situations, what equipment to use, where to compromise, and where to stick to a specific protocol, etc. We focused on methodology, and we practiced a lot. We moved through capture and processing of increasingly complex projects, and we received detailed handouts to supplement everything we were learning. The class also afforded students the opportunity to work on a larger group project; this January we captured a 3D model of a reproduction colossal Olmec head located outdoors at City College of San Francisco. CHI focuses on repeatability and process in order to achieve a robust, reproducible result.

Setting up for image capture at the January 2016 photogrammetry class; blogger Emily Frank is far left.

An added benefit of the class was the insight gained through conversation with the other students, who included museum photographers, landscape photographers, archaeologists, classicists, 3D-imaging academics, and the founder of a virtual reality start-up. This diversity fostered a breeding ground for inventive implementation, and the inevitable collaboration left me envisioning new ways to employ photogrammetry as a tool in my work.

For those of you who have ever considered the use of photogrammetry, I would strongly encourage you to sign up for one of CHI’s upcoming trainings. I still have a lot to learn and master, but I left the training with the feeling that with practice I would be able to capture and process 3D data with the accuracy and resolution to meaningfully contribute to the academic study of works of art.

Notes from CHI:

- Emily Frank has included a link to a 3D model of a reproduction colossal Olmec head located at City College of San Francisco. This huge outdoor sculpture was a practice subject in CHI’s January photogrammetry class in which our guest blogger Emily Frank was a participant. The model was created with photogrammetry, and it is presented on Sketchfab, a website for 3D models.

- See our Flickr photo album of the January 2016 photogrammetry class in which blogger Emily Frank participated.

Filed under: Commentary, Guest Blogger, News, On Location, Technology | Tags: ancient footprints, photogrammetry, Preservation

Sarah Duffy, PhD is a Postdoctoral Research Associate at the University of York in the Department of Archaeology. In May of 2013, after a series of storms, ancient footprints were revealed on a beach near Happisburgh (pronounced “Hays-boro”) on Britain’s east coast in Norfolk (see a 6-minute video). The footprints were fragile and washing away a little day by day. Sarah was called to the site by Dr. Nick Ashton, Curator of Palaeolithic and Mesolithic collections at the British Museum, to document it. Here is our interview with Sarah about this dramatic discovery.

CHI: Sarah, can you tell us how you got involved in the project and what you found when you arrived?

Sarah: It really came down to good timing and an opportune meeting of research colleagues. When the footprints were discovered, I had just begun working with Dr. Beccy Scott at the British Museum on a project based in Jersey called “Ice Age Island”. Beccy and my partner, Dr. Ed Blinkhorn, another early prehistoric archaeologist, have collaborated for many years, and he introduced us. During the week of the discovery, Beccy happened to be at a research meeting with Dr. Nick Ashton and suggested that he get in touch with me about the Happisburgh finding.

The next day, I received a call from Nick who asked if I would be able to take a trip to Norfolk to record some intertidal Pleistocene deposits at Happisburgh. Having just completed my PhD thesis (a “dissertation” in US currency), I was up for an adventure and ready to take on the challenge, and so I was on a train to the southeast coast two days later.

My first plan of action was to figure out how on earth you pronounced the name of the site! The next step was to figure out what equipment I would need to have available when I arrived. This proved somewhat challenging, as I had never visited the Norfolk coast, and it seems quite humorous in hindsight that one of the pieces of kit I requested was a ladder.

All of this said, the urgency to get the site photographed became clear when I showed up one very rainy afternoon in March. Standing on the shore, I felt very privileged to have been invited to record such an important set of features, which disappeared within only weeks of their discovery by Dr. Martin Bates.

CHI: What were your goals in the project and why did you choose to shoot images for photogrammetry? Can you tell us a little bit about your approach?

Sarah: Since I wasn’t sure what to expect when I reached the site, I took both photogrammetric and RTI kit materials with me. I intended to capture the 3D geometry of the prints with photogrammetry and subtle surface relief with RTI. However, when I arrived, both the weather and tidal restrictions limited the time we were able dedicate to recording. I therefore focused my efforts on photogrammetry, which proved a flexible and robust enough technique that we were able to get the kit down the cliff side in extremely challenging conditions and capture images that were used later to generate 3D models.

Based on the looming return of the tide and the amount of time required to prepare the site, our window of access was quite small. While I took the images, aided by Craig Williams and an umbrella, the rest of the team battled the rain and tide by carefully sponging water from the base of the features. As mentioned, I originally intended to capture images from above the site using a ladder. However, as the ladder immediately sank into the wet sand, I was forced to find other means of overhead capture: namely Live View, an outstretched arm, and umbrella. There was just enough time to photograph the prints, loosely divided into two sections, using this recording approach before we had to retreat back up to the top of the cliff (and to a very warm pub for a much deserved fireside pint!).

CHI: When you got back to your office, how long did it take you to process the images, and what software did you use?

Sarah: Originally, I used the Standard Edition of PhotoScan by Agisoft, later returning to the image set in order to reprocess it with their Professional Edition. PhotoScan’s processing workflow is relatively straightforward, and the time required to generate geometry is somewhat dependent on the hardware one has access to. The post-processing of the images was by far the most time-consuming component of the processing sequence. Since the software looks for patterns of features, there was a substantial amount of image preparation that needed to be completed first, before models could be produced. For example, rain droplets on the laminated surface that contained the prints needed to be masked out, as well as the contemporary boot prints that accumulated in the sand that surrounded the site throughout the image sequence.

CHI: How were the 3D models you produced used by the other archaeologists involved with the site?

Sarah: Once the models had been generated, the rest of the team, including Nick Ashton, Simon Lewis, Isabelle De Groote, Martin Bates, Richard Bates, Peter Hoare, Mark Lewis, Simon Parfitt, Sylvia Peglar, Craig Williams, and Chris Stringer, wrote the paper on the results. Nick Ashton and Isabelle De Groote closely analyzed the models of the prints in order to study size, movement, direction, and possible age of the early humans who might have created these features. Isabelle later worked with the 3D printing department at Liverpool John Moores University in order to have one of the digital models printed.

CHI: Since the footprints were washed away, your images are the best record of the site that exists. Are the 3D models accessible? What will you do to preserve this material?

Sarah: Coverage of the footprints, including excerpts of the digital models that I generated and the 3D printout, can be viewed at the Natural History Museum exhibit in London, Britain: One Million Years of the Human Story, which closes September 28th. Findings from the analysis have also been published in PLOS ONE, an open-access, peer-reviewed scientific journal.

As mentioned, when I visited the site last March, I had hoped to undertake a RTI survey. Although conditions on the day of recording did not permit multi-light capture, I have since been able to generate virtual RTI models that reveal the subtle topography of the prints. An excerpt of one of these models can be viewed on my website.

Additionally, the research team, in collaboration with the Institute of Ageing and Chronic Disease at Liverpool, are currently working on extracting further information from the image set. Findings from this work will be made available in the future. Once analysis is complete, the images and resulting models will be archived with the British Museum.

CHI: Thank you for your time, Sarah, and what a great story!

Sarah Duffy has been collaborating with Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI), including taking CHI’s training in Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) and working with the technique since 2007 while she was a graduate student in Historic Preservation at the University of Texas at Austin. Sarah authored a set of guidelines for English Heritage on RTI. During her doctoral work, she also began to apply her imaging skills in the area of photogrammetry.