Filed under: 3D, Equipment, Lighting, On Location, photogrammetry, RTI | Tags: Maori weaving, photogrammetry, RTI, TeRa

In January 2020 Mark Mudge and I traveled to the British Museum in London to document the only existing Māori canoe sail of its kind, made over 200 years ago. The imaging work was performed in collaboration with the New Zealand project Te Rā – The Māori Sail Whakaarahia anō te rā kaihau! – Raise up again billowing sail! funded by The Royal Society – Te Apārangi Marsden Fund.

The New Zealand team produced a 13½-minute video of the project that you can watch here: Imaging Te Rā at the British Museum 2020

helps prepare the sail for imaging

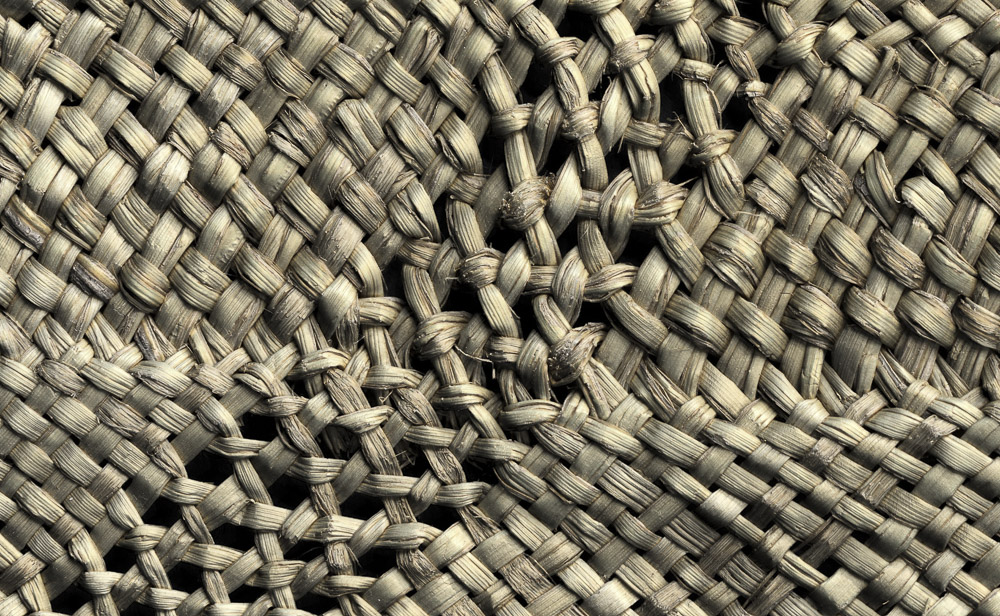

The construction and materials of the last known Māori sail, Te Rā, had not been identified, documented, or made publicly available, until this project put significant efforts into these identifications and documentation. Māori textile researchers from New Zealand brought in CHI to image the sail, which is made with fragile plant materials and feathers. The CHI team used both photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to help the experts examine and understand more about the delicately woven and perishable materials. The research team wanted to gain a greater understanding of how the Māori sailed the ocean and the intricacies of their weaving techniques.

We worked with the sail on site at the British Museum for 5 days.

The first day was all preparation: meeting the team, examining the sail, setting up equipment, testing lights, and troubleshooting. The second day was spent on the imaging. The initial preparation had begun back in the CHI studio in San Francisco, when Marlin Lum, Imaging Director, prepared for the intensive imaging project by creating a life-size paper template of the sail so the CHI team could work out the imaging logistics ahead of time. Marlin had also created an ingenious camera rig to manage the imaging and protect the fragile materials. Marlin’s rig was attached to a rental pro video slider unit that we picked up in London on the first morning.

At the museum collection facility, the sail was spread out on a protective foam core platform on the floor, covered by black paper. Because the sail has a pattern of holes in it, we performed tests on how best to mask out the holes so that they would be correctly modeled as holes in the final model. The black paper worked best. Over this the team positioned the trolley with its cantilevered arm that could move across and incrementally shoot the entire area, photo by photo. The camera height could be adjusted using a slider and the camera angle could be adjusted using a ball head.

Here is my project note from the morning of the second day:

“Light tests and light adjustments are done. We add a Speedlite to the mix of lights to deal with a corner that was a bit dark. We will trigger the Speedlite (Michael’s Canon 600) with the PocketWizard TT1 and TT5 combo and all 4 Monoblocks are set to slave mode. It takes a bit of time to tune everything in using the light meter and small adjustments. We feel now the entire sail is evenly lit and imaging can begin.”

Scale bars were placed around the small end of the sail as were color checkers. Using a Canon 5DSR with 24mm f2.8 IS USM lens, and shooting at 18 inches distance from the subject, the imaging began with a calibration pass with 90-landscape-270 rows – then returned to the 90 position for the remainder of the imaging in that pass.

The feathers that trim the sail presented a significant imaging challenge: they stick up, and there are knots and places where the material juts out. The camera focus was set manually to allow some extra depth of field above where the main body of the sail was laid out, so that these elements would remain in focus.

As the work progressed, I recorded this:

“We completed the second pass of the sail with a 50mm lens today and shot 3 RTIs of detail areas chosen by Donna from the Maori textile team. Then we had a crew come in to turn the sail over, and we prepped everything for the back side (which is actually more important for the weavers). We will begin shooting that first thing tomorrow.”

Image: © TeRa Project, Marsden Fund, 2020:

After completing the work on site each day, we returned to our London apartment and began the next step: processing the images of the sail. We have built the RTIs and some other high-resolution 2D outputs of the sail and shared them with the team. The detail is fantastic. We look forward to the team’s continued research and the publishing of their findings, along with our imaging results.

Special thanks to: Donna Campbell, co-Principle Investigator (co-PI) for the research project worked closely with us on site; Julie Adams, Curator of the Oceania Collections at the British Museum, hosted the imaging project; Michael O’Neill, a photographer from the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa; Kira Zumkley, a London-based heritage photographer and researcher; and Jill Hassell, museum assistant. Catherine Smith, co-PI on the project aided in logistics and overall project management.

You can read more about the sail in the research team’s blog and also the British Museum’s description of the sail from its online collection.

Filed under: 3D, Guest Blogger, On Location, photogrammetry, Training, Workshops

In October 2019, our training team at CHI delivered a 4-day photogrammetry class for staff at the Library of Congress (LoC) in Washington, D.C. The class was part of a pilot project to test the use of photogrammetry for building digital models of three-dimensional items held in the Library’s collections. Eileen Jakeway, innovation specialist in Digital Strategy at the LoC, wrote a blog about it. Check it out!

The Library also released some 3D models, including a cast of Abraham Lincoln’s hand (this is CHI’s snapshot of the model).

Filed under: Equipment, Guest Blogger, photogrammetry, Technology, Training, Workshops

Christopher Ciccone is a photographer at the North Carolina Museum of Art, and this is a post he wrote for the museum’s blog Circa. Chris attended the 4-day photogrammetry training class taught by the CHI team at the museum in May 2018 and describes the experience here. Thank you for sharing your blog, Chris!

Photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs of an object (or in aerial photogrammetry, a geographic area). This is done by taking a series of carefully plotted still photographs that incorporate targets of known size and then analyzing the images with specialized software. The resulting data can then be used to generate a variety of output products such as maps, detailed renderings, and 3-D models for use in a number of applications.

Dense point cloud rendering of sculptor William Artis’s Michael. The blue rectangles represent the position of the camera for each image that was used to create the 3-D model.

Although photogrammetry as a scientific measurement technique has existed since the nineteenth century, it has been the advent of digital photography and high-powered computational capacity that has made it a practical tool for scholars, researchers, and photographers. Because photogrammetry can be employed on objects of any size, its usefulness in the cultural heritage sector is vast. Interesting uses of photogrammetry include, for example, documentation of historic sites that might be slated for destruction or are in danger of ongoing environmental damage.

Photogrammetry at the NCMA

In May the Musem’s Photography and Conservation departments hosted instructors Carla Schroer and Mark Mudge from Cultural Heritage Imaging in San Francisco for a four-day photogrammetry training workshop. Participants included myself, NCMA Head Photographer Karen Malinofski, and NCMA objects conservator Corey Riley, as well as colleagues from the National Park Service and the University of Virginia.

Workshop participants Cari Goetcheus and Gregory Luna Golya photograph Willam Artis’s Michael on a turntable to facilitate views from all angles of the object.

William Ellisworth Artis, Michael, mid-to-late 1940s, H. 10 1/4 x W. 6 x D. 8 in., terracotta, Purchased with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest)

In the course of the class, we photographed several artworks in the Museum’s permanent collection, from a small bust by William Artis to Ledelle Moe’s monumental outdoor sculpture Collapse. The technique consisted of taking “rings” of overlapping photographs around the object, at optimal distance relative to focal length, with camera lenses set at a fixed focus point and aperture. The primary objective in each case was to establish a consistent, rule-based workflow in order to reduce the measurement uncertainty of the rendered photoset, which may then be used to generate reliable 3-D data as well as be archived and used for further study by others.

At the NCMA we plan to employ the technique for such projects as monitoring the surface wear over time of our outdoor sculptures, revealing surface markings of ancient objects for insight into makers’ techniques and tools, and generating 3-D renderings of delicate artifacts that can be manipulated and viewed in virtual environments by museum visitors and scholars. Other applications will become possible as 3-D processing tools are improved.

Will Rourk of the University of Virginia and NCMA Head Photographer Karen Malinofski photograph details of Collapse.