Filed under: 3D, Equipment, Lighting, On Location, photogrammetry, RTI | Tags: Maori weaving, photogrammetry, RTI, TeRa

In January 2020 Mark Mudge and I traveled to the British Museum in London to document the only existing Māori canoe sail of its kind, made over 200 years ago. The imaging work was performed in collaboration with the New Zealand project Te Rā – The Māori Sail Whakaarahia anō te rā kaihau! – Raise up again billowing sail! funded by The Royal Society – Te Apārangi Marsden Fund.

The New Zealand team produced a 13½-minute video of the project that you can watch here: Imaging Te Rā at the British Museum 2020

helps prepare the sail for imaging

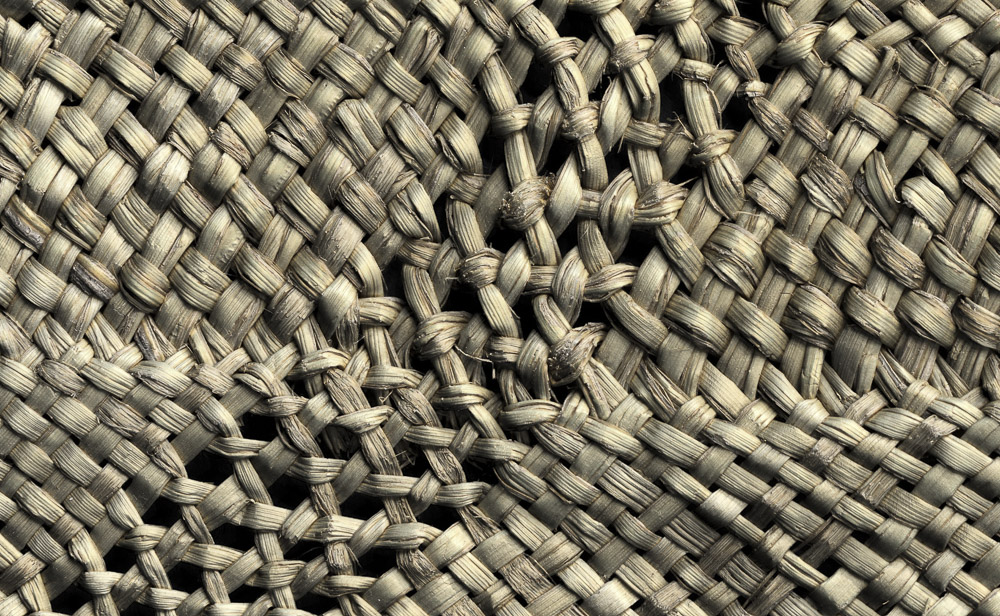

The construction and materials of the last known Māori sail, Te Rā, had not been identified, documented, or made publicly available, until this project put significant efforts into these identifications and documentation. Māori textile researchers from New Zealand brought in CHI to image the sail, which is made with fragile plant materials and feathers. The CHI team used both photogrammetry and Reflectance Transformation Imaging (RTI) to help the experts examine and understand more about the delicately woven and perishable materials. The research team wanted to gain a greater understanding of how the Māori sailed the ocean and the intricacies of their weaving techniques.

We worked with the sail on site at the British Museum for 5 days.

The first day was all preparation: meeting the team, examining the sail, setting up equipment, testing lights, and troubleshooting. The second day was spent on the imaging. The initial preparation had begun back in the CHI studio in San Francisco, when Marlin Lum, Imaging Director, prepared for the intensive imaging project by creating a life-size paper template of the sail so the CHI team could work out the imaging logistics ahead of time. Marlin had also created an ingenious camera rig to manage the imaging and protect the fragile materials. Marlin’s rig was attached to a rental pro video slider unit that we picked up in London on the first morning.

At the museum collection facility, the sail was spread out on a protective foam core platform on the floor, covered by black paper. Because the sail has a pattern of holes in it, we performed tests on how best to mask out the holes so that they would be correctly modeled as holes in the final model. The black paper worked best. Over this the team positioned the trolley with its cantilevered arm that could move across and incrementally shoot the entire area, photo by photo. The camera height could be adjusted using a slider and the camera angle could be adjusted using a ball head.

Here is my project note from the morning of the second day:

“Light tests and light adjustments are done. We add a Speedlite to the mix of lights to deal with a corner that was a bit dark. We will trigger the Speedlite (Michael’s Canon 600) with the PocketWizard TT1 and TT5 combo and all 4 Monoblocks are set to slave mode. It takes a bit of time to tune everything in using the light meter and small adjustments. We feel now the entire sail is evenly lit and imaging can begin.”

Scale bars were placed around the small end of the sail as were color checkers. Using a Canon 5DSR with 24mm f2.8 IS USM lens, and shooting at 18 inches distance from the subject, the imaging began with a calibration pass with 90-landscape-270 rows – then returned to the 90 position for the remainder of the imaging in that pass.

The feathers that trim the sail presented a significant imaging challenge: they stick up, and there are knots and places where the material juts out. The camera focus was set manually to allow some extra depth of field above where the main body of the sail was laid out, so that these elements would remain in focus.

As the work progressed, I recorded this:

“We completed the second pass of the sail with a 50mm lens today and shot 3 RTIs of detail areas chosen by Donna from the Maori textile team. Then we had a crew come in to turn the sail over, and we prepped everything for the back side (which is actually more important for the weavers). We will begin shooting that first thing tomorrow.”

Image: © TeRa Project, Marsden Fund, 2020:

After completing the work on site each day, we returned to our London apartment and began the next step: processing the images of the sail. We have built the RTIs and some other high-resolution 2D outputs of the sail and shared them with the team. The detail is fantastic. We look forward to the team’s continued research and the publishing of their findings, along with our imaging results.

Special thanks to: Donna Campbell, co-Principle Investigator (co-PI) for the research project worked closely with us on site; Julie Adams, Curator of the Oceania Collections at the British Museum, hosted the imaging project; Michael O’Neill, a photographer from the National Museum of New Zealand Te Papa Tongarewa; Kira Zumkley, a London-based heritage photographer and researcher; and Jill Hassell, museum assistant. Catherine Smith, co-PI on the project aided in logistics and overall project management.

You can read more about the sail in the research team’s blog and also the British Museum’s description of the sail from its online collection.

Filed under: 3D, Guest Blogger, On Location, photogrammetry, Training, Workshops

In October 2019, our training team at CHI delivered a 4-day photogrammetry class for staff at the Library of Congress (LoC) in Washington, D.C. The class was part of a pilot project to test the use of photogrammetry for building digital models of three-dimensional items held in the Library’s collections. Eileen Jakeway, innovation specialist in Digital Strategy at the LoC, wrote a blog about it. Check it out!

The Library also released some 3D models, including a cast of Abraham Lincoln’s hand (this is CHI’s snapshot of the model).

Filed under: RTI, Training, Workshops | Tags: Digital Imaging, RTI, RTIViewer, Training, Workshops

Marlin Lum is the Imaging Director at Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) and a member of the CHI training team.

Marlin Lum is the Imaging Director at Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) and a member of the CHI training team.

I thought I’d take a few moments to decode what it’s like to be an instructor in one of our RTI training classes. Like anything else, there’s a certain level of planning, intention, and positive enthusiasm that I expect from myself (and from anyone enrolled). I do my best to pass this on to everyone who elects to give us their valuable time. I truly enjoy teaching at this level. I see these training sessions as a unique opportunity to pass on my knowledge in a form that can help create conditions primed for discoveries as well as to make new friends.

RTI capture with iPhone in tow to track one of those special photographic moments. (Aviator sun glasses optional.)

CHI RTI training (as well as our photogrammetry class) simply means spending four days conveying photo DIY geekiness to a usually very enthusiastic, and sometimes even rowdy, motley crew of professors, scholars, conservation professionals, archaeologists, and pro photographers. (By the way, just so you know, it’s usually the archaeologists and the pro shooters who can hold the most liquor.) All of these folks, and everyone who walks into one of our trainings, is ultra-talented, focused, and very motivated to succeed. As you might guess, this makes my job significantly easier as well as seemingly more important. At least the furious note-taking in most of my hands-on demos would lead me to think this. As I always state on day one, hour one: “I make it my goal to make you successful (at least photographically).”

Got spheres? Get on the plane! Make sure those spheres are on same plane as the object. Place them carefully so they do not move and are always in focus.

Helping these trainees from the bus stop to the f-stop and along their way to making discoveries is not only a privilege but something of a rush. More than once I have witnessed the birth of an important discovery. I once watched a conservator realize that a Mayan lead ingot sitting on the bench actually had numerous coded “knot” inscriptions, though they were seemingly invisible to the human eye. RTI revealed this fairly matter of factly. I’ve heard the shriek of conservation staff as RTI revealed a previously hidden but somewhat “suspect” under-painting. I once heard an Egyptologist glyph expert read aloud, then carefully re-read, a good fortune spell. Apparently, the original person who had paid for the spell got taken, because RTI revealed that the original owner’s name had been scratched away and re-etched with a new dude’s name. I imagine that was a fairly common event. Wait till the guy dies, then sneak over there, scratch out his name, and write yours. Boom, check, all done, sweetie. All right there in stone — can’t deny that when the judge points a finger at you. The oohs and aahs I hear never disappoint.

Setting up the object for proper RTI capture can take a bit of time, but using Live View mode can help your troubles go away.

Here’s the gist: I get fired up when I see you guys get fired up. RTI has the potential to inspire. Materials and objects that you didn’t think were worth imaging suddenly land on the request list. One down side: I heard a pro shooter from a large institution complain that he didn’t need any more work (oh, sorry).

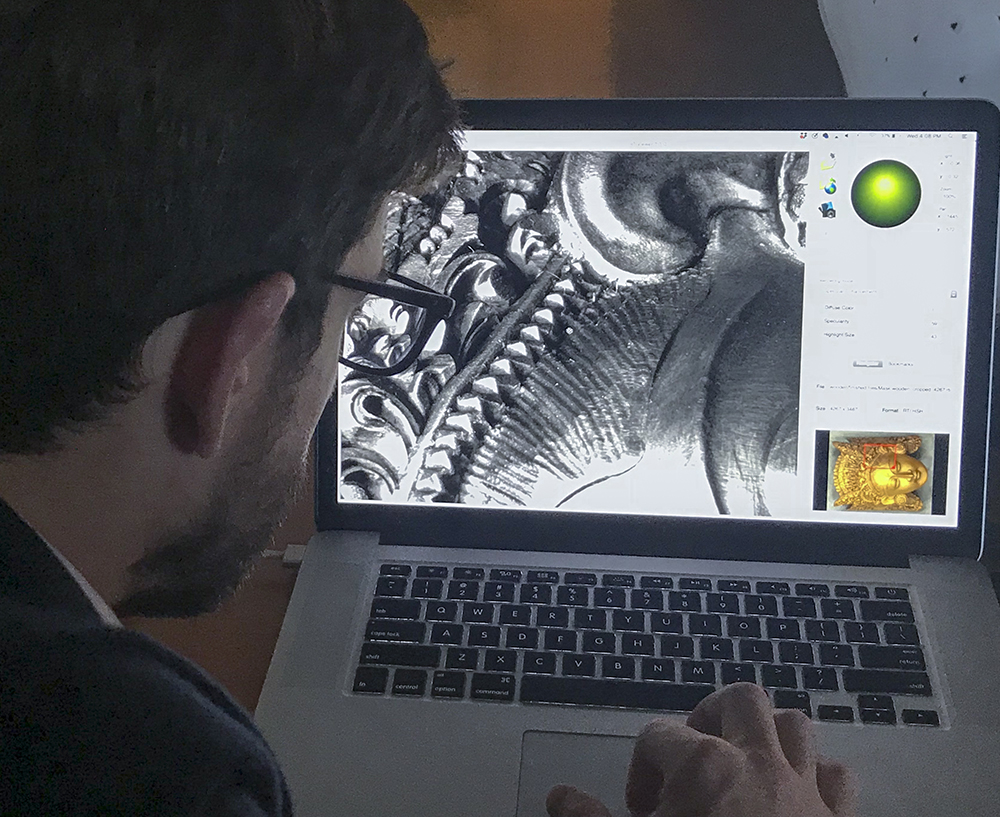

Use the RTIViewer to look at the details.

Just recently we taught an RTI class at the CHI studio (the photos in this blog are from that class). I’m not sure that any real discoveries were made, because we don’t have glyphs, ancient relics, masterpieces, or any “weird” non-provenance stuff from eBay lying around. However, I can vouch for the fact that I had a great time meeting cool new professionals, watching them engaged in what they do best, and then seeing them walk out the door, doing it better than before. Yup, I did write that. It’s in our best interest at CHI to make sure that you’re successful taking RTI (or photogrammetry) back to your professional crew.

Filed under: Equipment, Guest Blogger, photogrammetry, Technology, Training, Workshops

Christopher Ciccone is a photographer at the North Carolina Museum of Art, and this is a post he wrote for the museum’s blog Circa. Chris attended the 4-day photogrammetry training class taught by the CHI team at the museum in May 2018 and describes the experience here. Thank you for sharing your blog, Chris!

Photogrammetry is the science of making measurements from photographs of an object (or in aerial photogrammetry, a geographic area). This is done by taking a series of carefully plotted still photographs that incorporate targets of known size and then analyzing the images with specialized software. The resulting data can then be used to generate a variety of output products such as maps, detailed renderings, and 3-D models for use in a number of applications.

Dense point cloud rendering of sculptor William Artis’s Michael. The blue rectangles represent the position of the camera for each image that was used to create the 3-D model.

Although photogrammetry as a scientific measurement technique has existed since the nineteenth century, it has been the advent of digital photography and high-powered computational capacity that has made it a practical tool for scholars, researchers, and photographers. Because photogrammetry can be employed on objects of any size, its usefulness in the cultural heritage sector is vast. Interesting uses of photogrammetry include, for example, documentation of historic sites that might be slated for destruction or are in danger of ongoing environmental damage.

Photogrammetry at the NCMA

In May the Musem’s Photography and Conservation departments hosted instructors Carla Schroer and Mark Mudge from Cultural Heritage Imaging in San Francisco for a four-day photogrammetry training workshop. Participants included myself, NCMA Head Photographer Karen Malinofski, and NCMA objects conservator Corey Riley, as well as colleagues from the National Park Service and the University of Virginia.

Workshop participants Cari Goetcheus and Gregory Luna Golya photograph Willam Artis’s Michael on a turntable to facilitate views from all angles of the object.

William Ellisworth Artis, Michael, mid-to-late 1940s, H. 10 1/4 x W. 6 x D. 8 in., terracotta, Purchased with funds from the National Endowment for the Arts and the North Carolina State Art Society (Robert F. Phifer Bequest)

In the course of the class, we photographed several artworks in the Museum’s permanent collection, from a small bust by William Artis to Ledelle Moe’s monumental outdoor sculpture Collapse. The technique consisted of taking “rings” of overlapping photographs around the object, at optimal distance relative to focal length, with camera lenses set at a fixed focus point and aperture. The primary objective in each case was to establish a consistent, rule-based workflow in order to reduce the measurement uncertainty of the rendered photoset, which may then be used to generate reliable 3-D data as well as be archived and used for further study by others.

At the NCMA we plan to employ the technique for such projects as monitoring the surface wear over time of our outdoor sculptures, revealing surface markings of ancient objects for insight into makers’ techniques and tools, and generating 3-D renderings of delicate artifacts that can be manipulated and viewed in virtual environments by museum visitors and scholars. Other applications will become possible as 3-D processing tools are improved.

Will Rourk of the University of Virginia and NCMA Head Photographer Karen Malinofski photograph details of Collapse.

Christopher Ciccone is a photographer at the North Carolina Museum of Art.

Filed under: Conferences, Grants, Guest Blogger, Technology | Tags: 3D data, CHI, conservation, Digital Imaging, Digital Preservation, Open Source, RTI, symposium

Our guest blogger, Emily B. Frank, is currently pursuing a Joint MS in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and MA in History of Art at New York University, Institute of Fine Arts. Thank you, Emily!

With the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) back on the chopping block in the most recent federal budget proposal, I feel particularly privileged to have taken part in the NEH-funded symposium, Illumination of Material Culture, earlier this month.

Co-hosted by The Metropolitan Museum of Art and Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI), the symposium brought together conservators, curators, archaeologists, imaging specialists, cultural heritage and museum photographers, and the gamut of engineers to discuss and debate uses, innovations, and limitations of computational imaging tools. This interdisciplinary audience fostered an environment for collaboration and progress, and a few themes emerged.

(1) The emphasis among practitioners seems to have shifted from isolated techniques to integrating a range of data types.

E. Keats Webb, Digital Imaging Specialist at the Smithsonian’s Museum Conservation Institute, presented “Practical Applications for Integrating Spectral and 3D Imaging,” the focus of which was capturing and processing broadband 3D data. Holly Rushmeier, Professor of Computer Science at Yale University, gave a talk entitled “Analyzing and Sharing Heterogeneous Data for Cultural Heritage Sites and Objects,” which focused on CHER-Ob, an open source platform developed at Yale to enhance the analysis, integration, and sharing of textual, 2D, 3D, and scientific data. CHI’s Mark Mudge presented a technique for the integrated capture of RTI and photogrammetric data. The theme of integration propagated through the panelists’ presentations and the lightning talks, including but not limited to presentations by Kathryn Piquette, Senior Research Consultant and Imaging Specialist at University College London, on the integration of broadband multispectral and RTI data; Nathan Matsuda, PhD Candidate and National Science Foundation Graduate Fellow at Northwestern University, on work at NU-ACCESS with photometric stereo and photogrammetry; as well as a lightning talk by Chantal Stein, in collaboration with Sebastian Heath, Professor of Digital Humanities at the Institute for the Study of the Ancient World; and myself, about the integration of photogrammetry, RTI, and multiband data into a single, interactive file in Blender, a free, open source 3D graphics and animation software.

(2) There is an emerging emphasis on big data and the possibilities of machine learning.

Paul Messier, art conservator and head of the Lens Media Lab at the Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage, Yale University

The notion of machine learning and the possibilities it might unlock were addressed in multiple presentations, perhaps most notably in the “RTI: Beyond Relighting,” a panel discussion moderated by Paul Messier, Head of the Lens Media Lab, Institute for the Preservation of Cultural Heritage (IPCH), Yale University. Dale Kronkright presented work in progress at the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum in collaboration with NU-ACCESS that utilizes algorithms to track change to the surfaces of paintings, focusing on the dimensional change of metal soaps. Paul Messier briefly described the work being done at Yale to explore the possibilities for machine learning to work iteratively with connoisseurs to push data-driven research forward.

(3) The development of open tools for sharing and presenting computational data via the web and social media is catching up.

Graeme Earl, Director of Enterprise and Impact (Humanities) and Professor of Digital Humanities at the University of Southampton, UK, gave a keynote entitled “Open Scholarship, RTI-style: Museological and Archaeological Potential of Open Tools, Training, and Data,” which kicked off the discussion about open tools and where the future is heading. Szymon Rusinkiewicz, Professor of Computer Science at Princeton University, presented “Modeling the Past for Scholars and the Public,” a case study of a cross-listed Archaeology-Computer Science course given at Princeton in which students generated teaching tools and web content that provided curatorial narrative for visitors to the museum. CHI’s Carla Schroer presented new tools for collecting and managing metadata for computational photography. Roberto Scopigno, Research Director of the Visual Computing Lab, Consiglio Nazionale delle Richerche (CNR), Istituto di Scienza e Tecnologie dell’Informazione (ISTI), Pisa, Italy, delivered the keynote on the second day of the symposium about 3DHOP, a new web presentation and collaboration tools for computational data.

We had the privilege of hearing from Tom Malzbender, without whose work at HP Labs in the early 2000s this symposium would never have happened.

The keynotes at the symposium were streamed through The Met’s Facebook page. The other talks were recorded and will be available in three to four weeks. Enjoy!

Filed under: Guest Blogger, Technology, Training, Workshops | Tags: 3D data, conservation, photogrammetry, Training

Lauren Fair is Associate Objects Conservator at Winterthur Museum, Garden, & Library in Buffalo, New York. She also serves as Assistant Affiliated Faculty for the Winterthur/University of Delaware Program in Art Conservation (WUDPAC). Lauren was a participant in CHI’s NEH grant-sponsored 4-day training class in photogrammetry, August 8-11, 2016 at Buffalo State College. She posted an account of her experience in the class in her own blog, “A Conservation Affair.” Here is an excerpt from her fine post.

I have discovered the perfect way to decompress after a four-day intensive seminar on 3D photogrammetry: go to your friend’s cabin on a small island in a remote part of Canada. While you take in the fresh air and quiet of nature, you can then reflect on all that you have shoved into your brain in the past week – and feel pretty good about it!

I have discovered the perfect way to decompress after a four-day intensive seminar on 3D photogrammetry: go to your friend’s cabin on a small island in a remote part of Canada. While you take in the fresh air and quiet of nature, you can then reflect on all that you have shoved into your brain in the past week – and feel pretty good about it!

The Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI) team – Mark, Carla, and Marlin – have done it again, in that they have taken their brilliance and passion for photography, cultural heritage, and documentation technologies, and formulated a successful workshop on 3D photogrammetry that effectively passes on their expertise and “best practice” methodologies.

The course was made possible by a Preservation and Access Education and Training grant awarded to CHI by the National Endowment for the Humanities.

(Read the rest of Lauren’s blog here.)

This blog by Carla Schroer, Director at Cultural Heritage Imaging, was first posted on the blog site, Center for the Future of Museums, founded by Elizabeth Merritt as an initiative of the American Alliance of Museums.

My organization, Cultural Heritage Imaging (CHI), has been involved in the development of open source software for over a decade. We also use open source software developed by others, as well as commercial software.

What drove us to make our work open for other people to use and adapt?

We are a small, independent nonprofit with a mission to advance the state of the art of digital capture and documentation of the world’s cultural, historic, and artistic treasures. Development of technology is only one piece of our work–we are involved in many aspects of scientific imaging, including developing methodology, training museum and heritage professionals, and engaging in imaging projects and research. Because we are small, and because the best ideas and most interesting breakthroughs can happen anywhere, we collaborate with others who share our interests and who have expertise in using digital cameras to collect empirical data about the real world.

Our choice to use an open source license with the technology that is produced in this kind of collaboration serves both the organizations involved in its development and the adopters of the software. By agreeing to an open source license, the people and institutions that contribute to the software development are assured that the software will be available and that they and others can use it and modify it now and in the future. It also keeps things fair among the collaborators, ensuring that no one group exploits the joint work.

How does open source benefit its users?

It’s beneficial not just because the software is free. There is a lot of free software that is distributed only in the “executable” version without making the source code available to others to use and modify. One advantage to users who care about the longevity of their data − and, in our case, images and the results of image processing − is that the processes being applied to the images are transparent. People can figure out what is being done by looking at the source code. Also, making the source code available increases the likelihood that software to do the same kind of processing will be available in the future. It isn’t a guarantee, but it increases the chances for long-term reuse. Finally, open source benefits the community of people all working in a particular area, because other researchers, students, and community members can add features, fix errors, and customize for special uses. With a “copyleft” license, like the Gnu General Public License that we use, all modifications and additions to the software have to be released under this same license. This ensures that when others build on the software, their modifications and additions will be “open” as well, so that the whole community benefits. (This is a generalization of the terms; read more if you want to understand the details of a particular license.)

Open source is a licensing model for software, nothing more. The fact that it is “open” tells you nothing about the quality of the software, whether it will meet your needs, whether anyone is still working on it, how difficult or easy to learn and use it is, and many other questions you should think about when choosing technology. The initial cost of software is only one consideration in adopting a technology strategy. For example, what will it cost to switch to another solution, if this one no longer does what you need? Will you be left with a lot of files in a proprietary format that other software can’t open or use?

That leads me to remark on a related issue– open file formats. Whether you choose to use commercial software or open source software, you should think about how your data and resulting files will be stored and used. Almost always, you should choose open formats (like JPEG, PDF, and TIFF) because that means that any software or application is allowed to read and write to the format, which protects the reuse of the data in the long term. Proprietary formats (like camera RAW files and Adobe PSD files) may not be usable in the future. The Library of Congress Sustainability of Digital Formats web site has great information about this topic.

At Cultural Heritage Imaging, we use an open source model for development of imaging software because it helps foster collaboration. It also provides transparency as well as a higher likelihood that the technology and resulting files will be usable in the future. If you want to learn more about our approach to the longevity and reuse of imaging data, read about the Digital Lab Notebook.

Filed under: Guest Blogger, Technology, Training | Tags: 3D data, conservation, photogrammetry, Training

Our guest blogger, Emily B. Frank, is currently pursuing a Joint MS in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and MA in History of Art at New York University, Institute of Fine Arts. Thank you, Emily!

I’ve been following the development and improvement of photogrammetry software for the past few years. As an objects conservation student with a growing interest in the role of digital imaging tools in the study and conservation of art, I’ve always found photogrammetry of theoretical interest. In my opinion, until recently the limited accuracy of the software and tools impeded widespread applications in conservation. With recent advances, this is no longer the case; sub 1/10th mm accuracy has changed the game.

This January, the stars aligned and I was able (and lucky) to participate in CHI’s January photogrammetry training. From January 11 to 14, I lived and breathed photogrammetry in CHI’s San Francisco studio. The four-day course was co-instructed by Carla Schroer, Mark Mudge, and Marlin Lum, who each brought something extraordinary to the experience.

For those of you that don’t know them personally, I’ll provide context; these guys are total gurus. Carla brings business and tech know-how from years of work in Silicon Valley earlier in her career. She has a warm and direct teaching style that is accessible no matter what your photography/imaging background. Mark is a true visionary; he is rigorous and inventive, and always carefully pushing the brink of what’s possible. Marlin is the photographer of the group and a master at fabricating the perfect tool/workstation for the capture of near-perfect source images. His never-ending positivity is contagious. Together they are practically unstoppable. It’s obvious that they love teaching and truly believe in the power of the tools they are sharing.

The class began with a brief theoretical introduction, then dove into practical aspects of capture and processing. We swiftly covered how to approach a range of situations, what equipment to use, where to compromise, and where to stick to a specific protocol, etc. We focused on methodology, and we practiced a lot. We moved through capture and processing of increasingly complex projects, and we received detailed handouts to supplement everything we were learning. The class also afforded students the opportunity to work on a larger group project; this January we captured a 3D model of a reproduction colossal Olmec head located outdoors at City College of San Francisco. CHI focuses on repeatability and process in order to achieve a robust, reproducible result.

Setting up for image capture at the January 2016 photogrammetry class; blogger Emily Frank is far left.

An added benefit of the class was the insight gained through conversation with the other students, who included museum photographers, landscape photographers, archaeologists, classicists, 3D-imaging academics, and the founder of a virtual reality start-up. This diversity fostered a breeding ground for inventive implementation, and the inevitable collaboration left me envisioning new ways to employ photogrammetry as a tool in my work.

For those of you who have ever considered the use of photogrammetry, I would strongly encourage you to sign up for one of CHI’s upcoming trainings. I still have a lot to learn and master, but I left the training with the feeling that with practice I would be able to capture and process 3D data with the accuracy and resolution to meaningfully contribute to the academic study of works of art.

Notes from CHI:

- Emily Frank has included a link to a 3D model of a reproduction colossal Olmec head located at City College of San Francisco. This huge outdoor sculpture was a practice subject in CHI’s January photogrammetry class in which our guest blogger Emily Frank was a participant. The model was created with photogrammetry, and it is presented on Sketchfab, a website for 3D models.

- See our Flickr photo album of the January 2016 photogrammetry class in which blogger Emily Frank participated.

Filed under: Guest Blogger, On Location, Technology | Tags: Archaeology, biofilm removal, bronze, Lydia, Roman, RTI, Sardis

Our guest blogger, Emily B. Frank, is a student conservator on the Sardis Archaeological Expedition. Currently she is pursuing a Joint MS in Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works and MA in History of Art at New York University, Institute of Fine Arts. Thank you, Emily!

Sardis, the capital city of the Lydian empire in the seventh and sixth centuries BC, is often best remembered for the invention of coinage. Remains of a monumental temple of Artemis, begun during the Hellenistic period and never finished, still stand tall today. In Roman times, the city was famous as one of the Seven Churches of Asia in the Book of Revelation. In the fourth and fifth centuries AD, Sardis boasted what is still the largest known synagogue in antiquity. Sardis flourished and continued to grow in the Late Roman period until its decline by the seventh century AD.

Archaeological excavations at Sardis began over a century ago and are currently led by Dr. Nicholas D. Cahill, professor of Art History at the University of Wisconsin, Madison. The excavated material is vastly diverse and the conservation efforts there equally so. Conservation this season, under Harral DeBauche, a third-year conservation student at New York University, Institute of Fine Arts, supported active excavation across over 1,000 years of antiquity and addressed a number of site preservation issues. RTI greatly benefited the conservators and archaeologists in a couple of significant ways.

Significant finds with extremely shallow incised designs/inscriptions and impressions were made legible with RTI. RTI was helpful in understanding a bronze triangle recovered from the corridor of a Late Roman house (Fig. 1).

The triangle is incised with three images of a female deity and a border of magical signs (Fig. 2). Its use is likely connected with religious ritual practice in Asia Minor between the third and sixth centuries AD.

The legibility of the inscriptions, aided by RTI, reinforced the connection between the triangle’s inscriptions and material and written sources. Two comparenda for the triangle, one from Pergamon and one from Apamea, were identified, and the magic symbols on the triangle were connected with rituals described in a the Greek Magical Papyri. RTI also aided in decoding and documenting a lead curse tablet and in understanding the weave structure of bitumen basketry impressions.

Additionally, a multi-year biofilm removal project of the Artemis Temple at Sardis is currently underway, headed by Michael Morris and Hiroko Kariya, conservators in private practice. The removal of this biofilm is carried out by a six-day process. RTI was used experimentally to document the changes to the stone throughout the removal process (Fig. 3).

RTIs were taken before treatment, during treatment (day 3), and after treatment (day 7). Because the biocide continues to work for months after its application, a final RTI will be taken next summer. Initial comparison of the images showed no loss to the stone surface as a result of the biofilm removal process. All very exciting!

To find out more about the excavations at Sardis, see http://sardisexpedition.org/.

Filed under: Commentary, News, On Location | Tags: Digital Imaging, Digital Preservation, Training

I’m both proud of and a bit surprised by what we have been able to accomplish with a small team (and small budget) over the 21 years since our founding.

The best part of this work for me is getting to meet, collaborate with, learn from, and teach so many people with a love for art and history and culture. Every time we deliver training we learn from the people who take our classes. It doesn’t matter if they are full time photographers at a prestigious museum, or undergrads just getting started with photography. Every single person has something to share, a passion for something I don’t know about, a photography tip, a great story to tell.

Our most recent work collaborating with Indigenous communities is an honor. While we are the trainers with imaging skills to impart, we get the incredible opportunity to visit special locations and learn about objects meaningful to these communities. A Passamaquoddy petroglyph site in North East Maine is a special place. It’s not open to the public, in order to protect the fragile artwork. To spend time there and to hear the stories and explanations from Passamaquoddy people is an incredible gift.

This type of collaboration is synergistic. The folks we work with get new skills and a way forward to document their own material culture. Our greatest pleasure is in empowering communities to take control of their own cultural narrative. These culture bearers should be deciding what to document, how things are shared (or not shared) and what stories to tell along with them.

Overall, I am immensely grateful to be part of Cultural Heritage Imaging. So many people have contributed, supported us, advised us. Thank you all! We have an Acknowledgments page on our website, though it isn’t complete. We’ve had the opportunity to meet, and teach, and share knowledge with thousands of people over these 21 years. I look forward to every additional encounter.